Aghion Awarded Nobel Prize: An Analysis of His Creative Destruction Theory

The Nobel Prize's Quiet Warning to a World Afraid of the Future

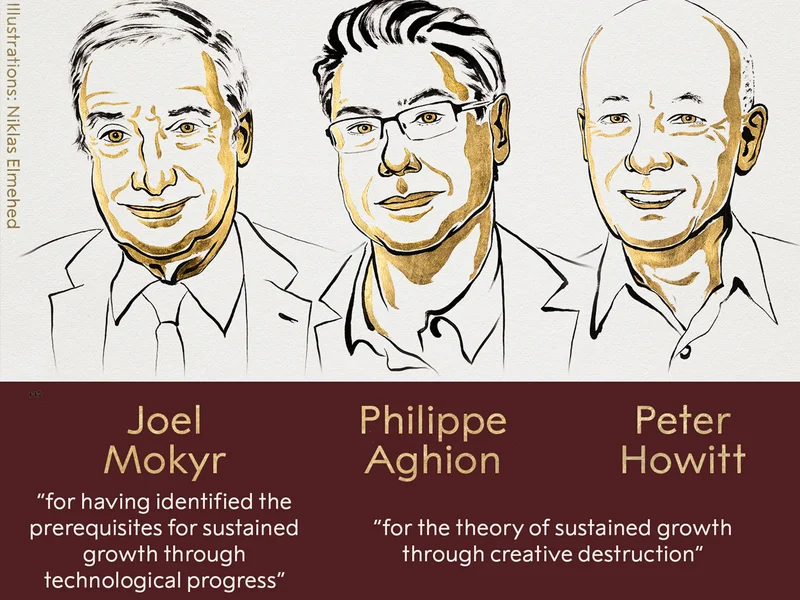

The announcement came, as it always does, with the requisite academic solemnity. Standing before a crisp blue backdrop, the Committee for the Prize in Economic Sciences in Memory of Alfred Nobel announced that the Nobel economics prize goes to 3 researchers for explaining innovation-driven economic growth: Joel Mokyr, Philippe Aghion, and Peter Howitt.

On the surface, it’s a standard-issue award for a foundational economic concept. But reading the announcement as just another academic honor is a severe misinterpretation of the data. The timing of this prize is the most critical variable. In a world grappling with the disruptive force of AI, re-emergent protectionism, and the immense power of tech monopolies, the Nobel committee didn't just award a prize. It sent a signal. This isn't a celebration of a settled theory; it's a stark, clinical reminder of the brutal trade-off at the heart of prosperity—a trade-off our current political climate seems determined to reject.

Deconstructing the Engine of Progress

To understand the warning, you first have to understand the mechanics of the theory. The work of these three laureates can be seen as two essential, interlocking components of a single engine.

Joel Mokyr, an economic historian, provides the engine’s foundational design—the why. His research digs into the historical soil of the Industrial Revolution to answer a simple question: why did it catch fire in 18th-century Europe and not fizzle out like countless earlier sparks of innovation? Mokyr’s answer is the distinction between two types of knowledge. For most of history, we had "prescriptive knowledge"—we knew that a certain crop rotation or metal-forging technique worked. This is like having a recipe. You can follow it, but you can’t improve it much beyond trial and error.

The breakthrough, Mokyr argues, was the rise of "propositional knowledge"—the scientific understanding of why it works. This is like knowing the chemistry of baking. With that deeper understanding, you can invent entirely new recipes. This scientific underpinning, combined with a culture that was (at least somewhat) open to new ideas challenging the old guard, created a self-sustaining feedback loop. Innovation wasn't a series of isolated accidents anymore; it became a cumulative process.

If Mokyr uncovered the engine's blueprint, then Philippe Aghion and Peter Howitt wrote the operating manual using the language of mathematics. They took Joseph Schumpeter's abstract 1940s concept of "creative destruction" and built a formal, predictive model around it. And this is the part of the theory that I find genuinely makes policymakers uncomfortable. Their framework shows, with cold precision, that sustained growth is inseparable from a constant, painful churn.

Their models illustrate a cycle: a firm innovates, gaining a temporary monopoly and the immense profits that come with it. Those very profits then become the target, the incentive for competitors to innovate something even better, displace the leader, and start the cycle anew. Growth isn't a gentle, rising tide. It's a series of controlled demolitions. It requires that we accept failure, displacement, and the obsolescence of entire industries and skill sets as a necessary feature, not a bug.

The Warning Label on the Prize

So, why award the prize for this specific idea now? The context is everything. We are living through what is likely the most significant wave of creative destruction since the Industrial Revolution, driven by artificial intelligence. Simultaneously, the political will to endure the "destruction" part of the equation is at an all-time low.

Look at the landscape. Aghion himself pointed to the "dark clouds" of protectionism (a clear reference to the ongoing trade disputes and nationalist economic policies). These policies are, at their core, an attempt to shield established domestic companies from the gales of creative destruction. They are a political choice to prioritize stability over dynamism, to protect the incumbents at the expense of the innovators. The Nobel committee is implicitly asking: at what cost?

The prize is worth 11 million Swedish kronor—to be more exact, about £867,000. But its intellectual value is in forcing a confrontation with the uncomfortable questions posed by the laureates' work. When governments talk about regulating AI, are they creating guardrails for progress or are they building walls to protect legacy jobs and companies that are, by Schumpeter's logic, destined for the scrap heap? When we lament the fall of old industries, are we mourning a loss or are we refusing to pay the price for the emergence of new ones?

Aghion and Howitt’s models show how competition drives the whole process forward. Yet we see the rise of "superstar firms," tech giants whose scale and network effects may be so vast that they risk choking off the next generation of innovators. As Aghion asked, "how can we make sure that today’s innovators will not stifle future entry and innovation?" This isn't an abstract academic query. It's the central regulatory question of our time. The Nobel committee just put it in lights.

The laureates' work demonstrates that sustained growth is not the default state of humanity; stagnation is. For most of history, economic life was a zero-sum game. The last 200 years have been the great exception, an outlier in the data set of human history. What if that exception was contingent on a social and political tolerance for disruption that we no longer possess? Are we prepared to manage the conflicts that arise from this churn, or will we allow the established interests—the ones with the lobbyists and the political capital—to block the path forward and guide us back to the mean of stagnation?

A Prize for a Theory We're Afraid to Practice

Ultimately, the 2025 Nobel Prize in Economics feels less like a celebration and more like an intervention. The committee is holding up a mirror, reflecting a deep and troubling paradox in our global culture: we demand the fruits of relentless innovation—longer lives, greater convenience, new cures—but we are increasingly unwilling to stomach the process that creates them. The work of Mokyr, Aghion, and Howitt isn't just a historical explanation or a mathematical model. It's a diagnosis of the engine of prosperity, delivered at a moment when we seem to be seriously considering pouring sugar in the gas tank. This award is a reminder that progress has a price, and it is always paid in the currency of disruption. The unspoken question hanging in the air is whether we still have the nerve to pay it.