OECD Data: What It Means for AI, GDP, and Global Health

Indian Health Professionals: Brain Drain or Global Gain?

The OECD just dropped its International Migration Outlook 2025 report, and while the headlines might focus on the overall dip in international student numbers (down 13% between 2023 and 2024), a deeper dive reveals a more complex, and frankly, more interesting story. Forget the visa clampdowns and housing market woes for a minute. Let's talk about doctors and nurses. Specifically, Indian doctors and nurses.

The Numbers Behind the Narrative

India is the top source of migrant doctors and second for nurses in OECD countries. That's not new information, but the scale of it is worth dwelling on. In 2020-21, there were 98,857 Indian-born doctors and 122,400 Indian-born nurses employed across OECD nations. To put it another way, between 2000 and 2021, the number of Indian-trained nurses working abroad jumped from approximately 23,000 to 122,000. Doctors? A similar trajectory, from 56,000 to nearly 99,000. That's a 435% increase for nurses and a 76% rise for doctors.

And here’s a figure that really makes you think: in 2021-23, OECD member countries had 606,000 foreign-trained doctors. Of those, 75,000 (12%) were India-trained. For nurses, the numbers are even starker: 733,000 foreign-trained nurses, with 122,000 (17%) coming from India. Indian doctors and nurses form backbone of global health systems, says OECD report - Times of India

The UK, US, Canada, and Australia are the primary destinations. In 2021, the UK housed 17,250 India-trained doctors (23% of all foreign-trained doctors in the UK), while the US had 16,800 (8%). The UK also housed 36,000 India-trained nurses (18% of the foreign-trained nurses), while the US had 55,000 (5%).

Now, before we start patting ourselves on the back for being such welcoming nations, let's consider the other side of the coin. India is on the WHO’s Health Workforce Support and Safeguards List, which identifies countries facing critical workforce shortages. Are we essentially poaching vital medical personnel from a nation that desperately needs them? I've looked at hundreds of reports on this topic, and this is the part that I find genuinely puzzling. We talk about development aid and global health initiatives, but simultaneously benefit from a system that arguably exacerbates healthcare disparities.

The Ethical Tightrope Walk

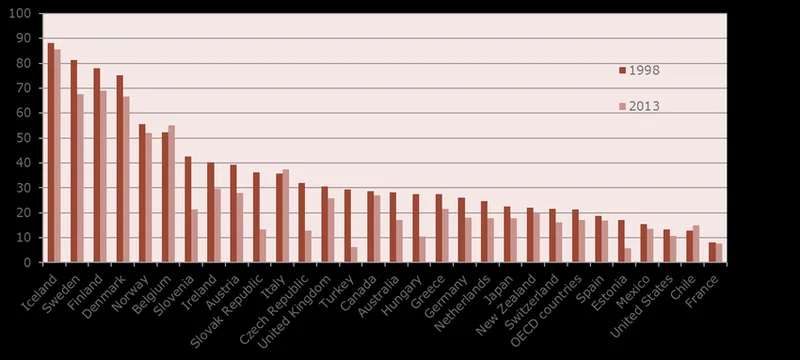

The OECD report doesn't explicitly address the ethical implications, focusing instead on the data trends. But the numbers paint a clear picture. While migration for family and humanitarian reasons is on the rise, the draw of skilled professionals, especially in healthcare, remains a significant factor. The report mentions streamlined licensing in the UK and fast-track credential recognition in Canada, but these policies, while efficient, raise questions about equity.

Consider this: OECD member countries house more than 830,000 foreign-born doctors and 1.75 million foreign-born nurses, representing about one-quarter and one-sixth of the workforce in each occupation, respectively. That reliance on foreign-trained professionals is only going to increase as populations age and healthcare demands rise.

The question becomes: how do we balance the need for skilled labor with the responsibility to support healthcare systems in developing nations? Is there a way to create a system that benefits both the receiving countries and the countries of origin? Perhaps through investment in training programs in India, tied to a commitment to return after a period of service abroad? Details on how these programs could be made work remain scarce, but the impact of inaction is clear.

Here’s a thought experiment: imagine a global healthcare system where doctors and nurses rotate through different countries, sharing expertise and resources. A bit utopian, maybe, but it highlights the potential for a more collaborative approach.

More Than Just Numbers

The OECD data is invaluable, but it's crucial to remember that behind each number is a person, a family, and a community. These are individuals seeking better opportunities, contributing to economies, and filling critical gaps in healthcare systems. They're not just data points on a spreadsheet.

The narrative often focuses on the economic benefits to the receiving countries – and those benefits are real. But what about the impact on the families and communities left behind? What about the potential for "brain drain" to undermine healthcare systems in countries like India? These are questions that require more than just statistical analysis; they demand a nuanced understanding of human motivations and global responsibility.